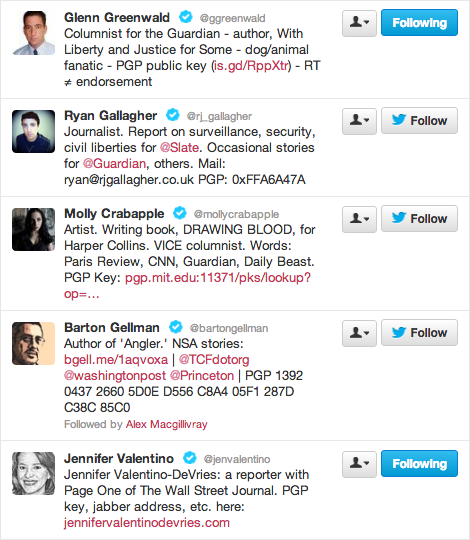

I’m thrilled to see so many more reporters using PGP, and putting their PGP key in their Twitter bios. The options to securely contact a reporter are tremendously increased over a year ago. However, not everyone is sharing their key in the safest way possible. I’d like to recommend that you tweet the fingerprint (not the shorter key id) of your PGP key. Here are some examples various ways people share their PGP keys today:

Some link to a copy of their key at an insecure HTTP URL. Some list their key id (e.g. 0DF7A097), which is insecure because it’s easy to generate a fake key with the same key id. Some, like @bartongellman, get it right and list their full forty-byte PGP key fingerprint: 1392 0437 2660 5D0E D556 C8A4 05F1 287D C38C 85C0. Others, like @jenvalentino, get it right by linking to a secure HTTPS URL under their own control (e.g. https://jennifervalentinodevries.com/).

Putting your full PGP key fingerprint in your bio is good for security, but wastes precious characters towards the maximum of 160 in your Twitter bio. Linking to a trusted HTTPS URL saves space, but not everyone has convenient access to a trusted site that serves HTTPS. I recommend a third option: Tweet the fingerprint (not the shorter key id) of your PGP key. Then put the permalink URL for that tweet in your Twitter bio. That leaves 132 more characters for the rest of your bio. Here’s an example:

To get the full character count you must update your bio using https://twitter.com/

Why is this approach better?

PGP makes it easy to find someone’s public key. There is a network of keyservers to which anyone can upload a PGP key with any email address. The hard part is, once you’ve retrieved a key, verifying whether it was the right one or a fake. A fake could be inserted at the keyservers, or it could be inserted in real time when you fetch the key, by a system like QuantumInject.

Once an attacker has put a fake key in the hands of your potential source, that attacker can use the fake key to conduct a man-in-the-middle attack, decrypting and then re-encrypting all of your emails between the two of you. The attacker would be able to read the content of your emails, but a correct-looking copy of the emails would still be delivered and decrypted as if nothing was wrong.

One way to verify a key’s authenticity is via the Web of Trust, a system that works somewhat like the party game Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon. Say Alice wants to verify Carol’s public key, but has no trusted communication channel to get it. If Alice knows that her friend Bob is also friends with Carol, and Alice has already verified Bob’s public key, Bob can send Alice a signed message that verifies which key actually belongs to Carol. PGP automates this network of signature checking to some extent, but it still requires human involvement for every signature, and there must be a chain of connections available between users for them to verify each others’ keys. Realistically, your potential source will be unable to verify your public key through the Web of Trust.

Fortunately there is an alternate system of trust: The Certificate Authority system used by web browsers verify trust in HTTPS web sites. This system is horribly broken in many ways, and places absolute trust in approximately 1500 authorities. However, it is miles better than nothing at all, which is what we get when we trust HTTP web sites to deliver correct information. And there are efforts to patch some of the CA system’s more glaring holes, such as Certificate Pinning, which Twitter takes advantage of when you access it via Chrome or via the native iPhone or Android apps.

When you use your Twitter bio to get your PGP key into Alice’s hands, Alice is implicitly trusting Twitter to send her the correct information about your key, and trusting HTTPS and the CA system to prevent a third party from modifying that information in transit. If you provide a link to a third-party web site, Alice additionally has to trust that site, plus any link shorteners you choose to use. And when that web site fails to provide HTTPS, nothing at all protects the authenticity of your key information in transit.

The safest and most efficient way to convey your PGP public key to the public is to tweet your public key fingerprint and link to that tweet in your bio.

Update 2013-11-01 7:25pm: @[eqe](https://twitter.com/eqe) [points out](https://twitter.com/eqe/status/396446065047527425) that gpg can take a fingerprint as an argument to `--recv-keys`, so you can choose provide a handy command for people to run. For example, “Get my PGP key by running ‘`gpg --recv-key E3E238BB9AE1D0226B400CAD3CBF8C99F1FAF31D`‘”.

Update 2013-12-10 5:35pm: gpg doesn’t actually validate the whole fingerprint in –recv-key:

After checking: gpg –recv-keys is insecure: gpg doesn't verify the response. Try hkp://imperialviolet.org:8080 as keyserver.

</p>

— Adam Langley (@agl__) December 11, 2013

</blockquote>